Posted on Tue, Feb. 12, 2008 NEW REPO METHOD | YOU DON'T PAY, CAR WON'T START Device puts ignition in creditors' hands JEFFERSON GEORGE

jgeorge@charlotteobserver.com

Staff Photographer

Beverly Byrd with her 1998 Oldsmobile Intrigue, which has a starter interrupt device. If she misses payments, the dealer can keep her car from starting. (LAYNE BAILEY — lbailey@charlotteobserver.com) |

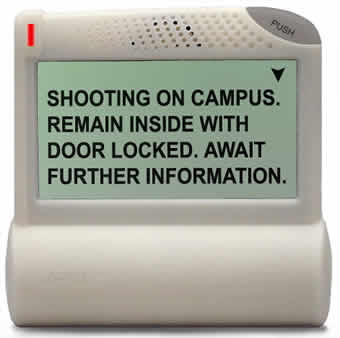

As the prices of used vehicles have increased, so have the potential losses for Carolinas auto dealers whose customers decide to skip their car payments. Instead of hiring more repo men, though, some dealers have a high-tech response to overdue bills that hints of Big Brother: an electronic system that remotely keeps a car from starting. Versions of starter interrupt devices have been around for about a decade, but better technology and greater concerns about customers' credit have led to more dealers equipping cars with the devices, which can cost a couple of hundred dollars each. "People see them as an insurance policy," said Ken Shilson, founder of the National Alliance of Buy Here, Pay Here Dealers, a trade group for dealers whose customers often have questionable credit and pay higher interest rates. "No question there's been a steep increase in the last 18 months." Shilson and dealers say starter interrupt devices won't turn a bad credit risk into a good one, but they reduce late payments and allow dealers to shift employees from collections. But one consumer protection agency said starter interrupt devices may put unfair pressure on buyers and deprive them of leverage in complaining about vehicle problems. The devices also could pose a safety risk by preventing a vehicle from starting at the wrong time -- when it has stalled in traffic, or if the owner is stranded in a dangerous area. Credit Quick Auto Sales began installing starter interrupt devices on cars at its five Charlotte-area lots about a year ago and has sold 1,200 to 1,300 vehicles equipped with the devices since then, said Keith Wilson, the company's general manager. Customers know about the device before buying, he said, and some are allowed to make late payments if they have a good explanation. "If there's a satisfactory commitment, you stay off the button," Wilson said. But if there's no communication or payment by the deadline, he said, "we're not going to sit here and wait until they feel like it." Still, the reality that their car could simply not start is hard for some buyers to accept. One Tuesday morning last month, Beverly Byrd's 1998 Oldsmobile Intrigue wouldn't start after she didn't make her full car payment of $154.54 on Monday. Byrd said she could pay only $85 because she had to buy medicine for her 21-year-old son after he had an asthma attack Sunday. Byrd had bought the car from Credit Quick in November, and she said the missed payment wasn't her first; a December bill was late when she accidentally wrote a check from a closed account. Even so, she was surprised her car was shut off after she paid part of her bill, showed a Credit Quick employee her son's pharmacy bills and promised to pay the rest in a few days. "You'd think this was a joke," Byrd said. "I feel so violated." After she paid the balance later that week, Byrd regained use of her car. Wilson said privacy laws prevent him from discussing specific customers. In general, he said, most buyers accept the starter interrupt devices as part of a deal, and the devices have reduced late payments. "If they do what they agree contractually to do," he said of customers, "they will never know this unit is on their car." Stemming dealers' losses About half of the nation's roughly 60,000 used-car lots are "buy here, pay here" operations, said Shilson, who also runs Subprime Analytics, a company that has studied about 334,000 loans worth about $2.7 billion. Of those, more than 25 percent have been written off by dealers, with a net loss of more than $376 million, the company's data shows.In the system used by Credit Quick and developed by Pay Technologies of Cleveland, Ohio, dealers access a secure Web site to send a signal through a pager network to a receiver in a car, said Jim Krueger, one of Pay Technologies' two owners. The device -- located under the dashboard -- doesn't shut off a car, he said, but rather keeps it from starting the next time. The company began selling starter interrupt systems in 2000, Krueger said, first offering a device that required dealers to give buyers a code after each payment. In that system, drivers entered the code into a keypad so the car would start. The computer-pager system, called WebTeck, came online in 2004, and Pay Technologies competes with a handful of other companies that also make starter interrupt devices. Interest in WebTeck grew with the value of used cars, Krueger said. "These are not almost-ready-to-go-to-the-dump vehicles," he said. Krueger wouldn't say how many customers his company has in the Charlotte region, saying only that it was more than 50. Each unit sells for $200 -- less for larger orders -- and only a few of every 1,000 fail, he said. The company hasn't measured how effective the devices are with collections, he said, but dealers say they have fewer people chasing down delinquent accounts. Shilson agreed, saying lenders can handle twice as many accounts because they can simply shut a car down instead of chasing a customer. "You're not dogging people. They have more urgency to pay you," he said. "If (a car) doesn't move, they've got a problem." Questions, but no complaints The Better Business Bureau of Southern Piedmont began getting calls about starter interrupt devices last year, president and chief executive Tom Bartholomy said. About a dozen people called with questions, he said, but no complaints. The Consumer Protection Division of the N.C. Attorney General's Office received only two calls about the devices and no written complaints last year, said Jennifer Canada, a spokeswoman for the state Justice Department. In Washington, though, the National Consumer Law Center sees the devices as "a growing concern" because of potential negative effects on buyers, said John Van Alst, a staff attorney at the center who previously worked with Legal Aid of N.C. The center works to protect people with low incomes, immigrants, former welfare recipients and others from being victimized by businesses. It regularly publishes consumer law manuals, including one on vehicle repossessions. In its 2005 manual on repossessions, the group wrote that the threat of a car being disabled could scare people into ignoring more important bills, and also make them afraid to withhold payments to protest problems with a car. Although many dealers say they don't want to shut a car down, Van Alst said, "it really is another device to put the fear into the consumer." Another issue is where a car is when a lender uses the starter interrupt device. A repo man usually confiscates a car at a person's home or job, Van Alst said, but the device could keep a car from starting anywhere. Some dealers say they wait until after midnight to disable a vehicle. But if the owner is away from home then, Van Alst said, "that could be even worse." These questions and others, he said, may not be answered outside a courtroom. To date, he said, only a handful of lawsuits across the country have challenged starter interrupt devices. "This is relatively new area," Van Alst said. "Most states haven't regulated this at all. ... There's no uniform understanding of where this is going to go." |

Stopwatch

Stopwatch

Los Angeles this week passed a controversial new tax that should impact city VoIP users, reports the

Los Angeles this week passed a controversial new tax that should impact city VoIP users, reports the

But what this really is, is a successor to the humble pager. Motorola had some success working the clamshell pager design into a phone years ago, if you remember the V100. This was a minor hit with teenagers before the Danger Sidekick came along, and cleaned up.

But what this really is, is a successor to the humble pager. Motorola had some success working the clamshell pager design into a phone years ago, if you remember the V100. This was a minor hit with teenagers before the Danger Sidekick came along, and cleaned up.

ATM300

ATM300

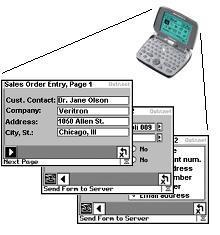

If you see someone in the field (like salespeople, technicians, and delivery people) using paper forms, their company could probably save a pile of money, and get much better timeliness, accuracy and efficiency, by using converting to Outr.Net's Wireless Forms. Custom applications for as little as $995, delivered in just a few days.Outr.Net has a web page on Wireless Forms for Timeports at:

If you see someone in the field (like salespeople, technicians, and delivery people) using paper forms, their company could probably save a pile of money, and get much better timeliness, accuracy and efficiency, by using converting to Outr.Net's Wireless Forms. Custom applications for as little as $995, delivered in just a few days.Outr.Net has a web page on Wireless Forms for Timeports at: